Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 2.23.2017

Book from: Personal collection

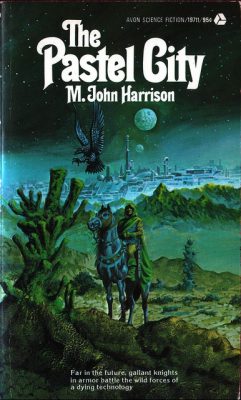

Cover art by the wonderfully named Gray Morrow

“Some seventeen notable empires rose in the Middle Period of Earth. These were the Afternoon Cultures. All but one are unimportant to this narrative, and there is little need to speak of them save to say that none of them lasted for less than a millennium, none for more than ten; that each extracted such secrets and obtained such comforts as its nature (and the nature of the Universe) enabled it to find; and that each fell back from the Universe in confusion, dwindled, and died …

tegeus-Cromis, sometime soldier and sophisticate of Viriconium, the Pastel City, who now dwelt quite alone in a tower by the sea and imagined himself a better poet than swordsman, stood at early morning on the sand-dunes that lay between his tall home and the gray line of the surf. Like swift and tattered scraps of rag, black gulls sped and fought over his downcast head. It was a catastrophe that had driven him from his tower, something that he had witnessed from its topmost room during the night.”

Such mixed feelings I have about this direst and 70’s-est of fantasy novels! On the one hand, who am I to say no to prose that is that dire, and that arch. (see: my obsession with Tanith Lee) Also on that hand, M. John Harrison’s blog is one of my favorites; I’m fascinated by his intellect and sensibilities. On the other hand, this is almost 50 years distant, the plot and characters are so silly and derivative (battles for the fate of an empire, the reassembly of a band of elite warriors in order to defend a beloved queen), and there are giant sloths that are meant to be taken seriously as noble and tragic creatures. I’m not sure even 12-year-old me could have managed that sentiment successfully.

Politically, this has a provocative flavor: anti-capitalist, anti-industrialist. The conceit of the setting is that numerous high-technological societies have ravaged the earth’s resources, and fallen, leaving crumbling medieval cities that harvest glowing, deadly technology from wastelands to wage intermittent wars. Remaining civilizations, namely Viriconium, are burdened by a sense of their own impending failure; entropy is the order of the day. Jack Vance’s Dying Earth is an obvious influence, and I assume there’s a lot of Moorcock in there too, but I still have yet to read any of his work. There’s also a lot of T. S. Eliot, sometimes pastiched very directly via the not-great poetry of tegeus-Cromis. (Sorry, Cromis.)

Aesthetically, let’s just say it: this book is fucking nuts. The main appeal of the book for me is really just Harrison’s visionary, desolate, cavernous nature-writing, which could so easily be translated to some kind of 2-hour-long Pink Floyd music video, and I wish somebody would. Here’s tegeus-Cromis, he of the nameless sword, traversing the rocky hills:

“In a day, he came to the bleak hills of Monar that lay between Viriconium and Duirinish, where the wind lamented considerably some gigantic sorrow it was unable to put into words. He trembled the high paths that wound over slopes of shale and between cold still lochans in empty corries. No birds lived there. Once he saw a crystal launch drift overhead, a dark smoke seeping from its hull.”

Continue reading The Pastel City, by M. John Harrison (1971) E