INCEST, the answer is incest.

If you’re marketing anything in the line of gothic horror, it takes a minimum of three words to establish that the big reveal is incest: “twins” and “no outsiders.”

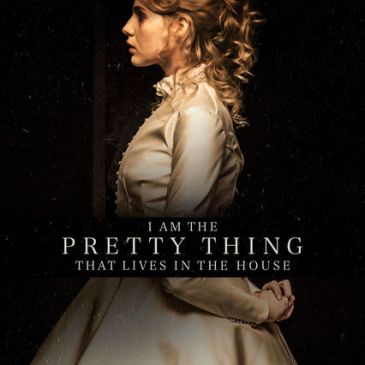

2017 Irish horror film The Lodgers is lusciously beautiful, slightly underbaked, and very much undercut in the suspense department if you happen to take the above deductive shortcut. The Gothic is one of the preeminent genres where obviousness doesn’t necessarily undercut efficacy – in fact, can easily be an asset, a piece of set dressing that evokes delicious foreboding. The Lodgers, though, suffers from a general sense of unrealized intensity and suspense: lukewarm chemistry among the actors, ghosts that are scary-ish at best, etc. This makes the hand-wringing over what ails those reclusive twins, and all the film’s other emotional stakes, all seem a bit empty or tedious, sometimes comically so.

That said, the film is atmospherically beautiful enough to be enjoyed purely on the basis of looks and sound. On those counts, it has the deeply satisfying sensory and emotional coherence of a fairy-tale pocket universe – the psychogeographic trinity of the haunted mansion, the deep woods, and the huddled village. I’ve also mentioned before my affinity for water-based imagery, and The Lodgers overfloweth with mists, depths, drowning phantoms, and surreal, gravity-defying drips.

Anglo-Irish twins Rachel and and Edward live in a decaying country mansion, governed by a set of nursery-rhyme rules (be in bed by midnight; no outsiders), surrounded by phantoms, and feared/scorned by the nearby villagers. The film opens on their 18th birthday, the brink of rupture: Edward is both traumatized by and deeply loyal to the legacy of their house and its rules, while Rachel is restless, defiant, and drawn to a young villager, Sean, who has recently returned from World War I.