Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 9.28.2020

Book from: Personal collection

In post-Arthurian Britain, the wars that once raged between the Saxons and the Britons have finally ceased. Axl and Beatrice, an elderly British couple, set off to visit their son, whom they haven’t seen in years. And, because a strange mist has caused mass amnesia throughout the land, they can scarcely remember anything about him. As they are joined on their journey by a Saxon warrior, his orphan charge, and an illustrious knight, Axl and Beatrice slowly begin to remember the dark and troubled past they all share.

The Buried Giant has the slow-motion horror of a nightmare: the confused repetitiousness of the dialogue; Axl and Beatrice’s frailty and tentativeness; the blurred, clouded landscape; the increasing sense of building towards a terrible revelation or shattering. As is typical of Ishiguro, the prose is carefully flat and affectless: an acres-wide, inch-deep pool of water, any ripples almost imperceptible. To be blunt, the prose is boring—and yet I also kept thinking that this was the most entrancingly, sublimely boring book I’ve ever read. I felt like Beatrice in the scene where she’s swarmed by rat-like, life-stealing pixies and nearly subsides into death. Slow-motion horror.

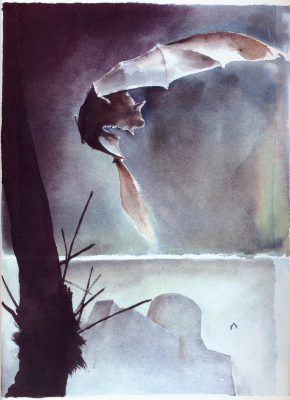

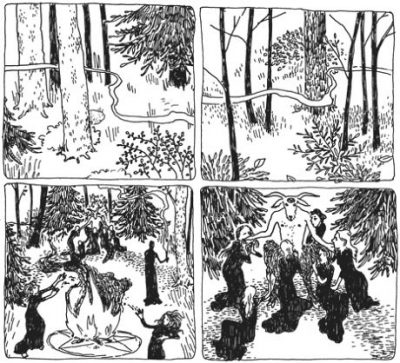

I was transfixed by these outbreaks of folk horror: the woman stroking a rabbit’s fur with a knife in a rain-dripping ruin, the underground beast described as looking something like “a large skinless animal,” the tunnels full of infant skeletons. As indelible as these images are—like Symbolist paintings—they become indescribably more disturbing because of the way that Ishiguro doesn’t describe them head-on. He robs us of a sense of clarity, control—the narrator’s vision is always glancing away, blurring at the edges.

The gradual revelation of mass slaughter that arises from these grotesque suggestions, and the slow topple towards renewed slaughter, is almost unbearably tragic, tearing. Ishiguro establishes his main characters as tragicomically human: vulnerable, bumbling, striving, absurd, valiant, kind. Then he shows us that they are walking towards a point of no return. There will be no reconciliation, no peace for the land, once the Buried Giant rises. Saxons will fight Britons once more; Axl and Beatrice fear the permanent oblivion of an afterlife with no kindness toward lovers. Companionship and love, hard-earned, will fade into another generation of helpless loss and strife. Did it all matter, that they loved? Of course it does: over the course of the novel, we see how much it matters to them, and to us, that these characters loved. But in the eyes of history, it does not.

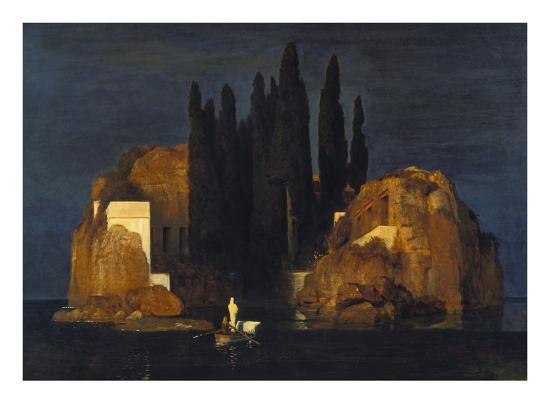

The Isle of the Dead, 1880 version, Arnold Böcklin

The Isle of the Dead, 1880 version, Arnold Böcklin

Related reading:

The Remains of the Day, by Kazuo Ishiguro (1989): review by Emera

The Ballad of Sir Dinadan, by Gerald Morris (2003): review by Emera