Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 7.23.2017

Book from: Personal collection

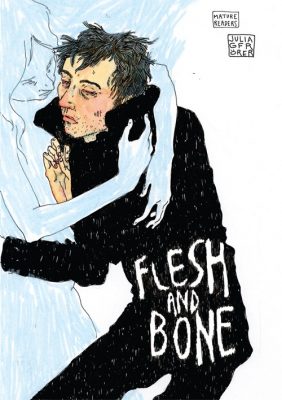

A scintillating and sensual novel about a young woman’s ingress into a fantastically strange family.

The hand of the young woman in question has been promised to the scion of a noble family. She is to make her preparations for marriage at the family’s villa, whose inhabitants have a fear of the night, books, sadness, and anything that smacks of disorder. There the unnamed young bride will be initiated into the art of seduction and will learn, one by one, each of the family secrets.

In this erotically charged and magical novel, Alessandro Baricco portrays a cast of mysterious characters who exist outside of the rules of causation as he tells a story, an adult fable, about fate, sex, family, love and the difficult job of being together.

This short novel is exquisite but arguably vacuous, depending on your tolerance/appetite for flighty, languid aristocratic types afflicted by mysterious ailments of the heart. Said type, plus dreamy surrealism, plus etc. is normally so much my thiiiing in fiction that Kakaner laughed at me, deservedly, when I picked this up at the bookstore and showed her the cover-flap copy. If you like Anaïs Nin, if you like Rikki Ducornet, this book has a seaside villa near their work. Also, actually, Wes Anderson, in the dwelling on rich people’s [over]subtle troubles and the interest in simultaneously lavish and fussy ritual.

But gawd, this book tried even my patience for featherily virtuosic writing and languorous sorrows. The glowy feeling of mystery is appealing – including that drifting obscuringly around the novel’s metafictional narrator, a nameless writer who is diverting him/herself with the work of writing this novel, while ruminating on the aftermath of some kind of immense (we’re told) sorrow and being snippy at a psychoanalyst. The Young Bride – plucky, down on her luck, a quiet survivor – is a likable-by-default protagonist, sharp and genuine enough to provide ballast for the rest of the cast, about whom one must ask repeatedly, “Are any of your problems even real?”

What ultimately tipped me over from mild skepticism into outright objection was the baffling pose that the book adopts towards women and prostitution. I tried for a while not to judge it purely along that axis, in the hopes that Baricco was going to do something more nuanced with it, but in the end I did find just stupid and piggish his narrative device of delivering nearly all of his female characters into prostitution (or discovering them there to begin with) as a sort of ultimate formative experience. Excuse me, but fuck that.

I would read this again just for the luxuriant sensations of the prose, and for the writing about writing, but the narrative content is a big ??? for me.

On the plus side, here’s my favorite passage from the narrator-writer:

I’ve noticed that, more than in the past, I like letting [my book] glide off the main road, roll down unexpected slopes. Naturally I never lose sight of it, but, whereas working on other stories I prohibited any evasion of this type, because my intention was to construct perfect clocks, and the closer I could get them to an absolute purity the more satisfied I was, now I like to let what I write sag in the current, with an apparent effect of drifting that the Doctor, in his wise ignorance, wouldn’t hesitate to connect to the uncontrolled collapse of my personal life, by means of a deduction whose boundless stupidity would be painful for me to listen to. I could never explain to him that it’s an exquisitely technical matter, or at most aesthetic… It’s a question of mastering a movement similar to that of the tides: if you know them well you can happily let the boat run aground and go barefoot along the beach picking up mollusks or otherwise invisible creatures. You just have to know enough not to be surprised by the return of the tide, to get back on board and simply let the sea gently raise the keel, carrying it out to sea again. With the same ease, I, having lingered collecting all those verses of Baretti’s and other mollusks of that type, feel the return, for example, of an old man and a girl, and I see them become an old man standing stiffly in front of a row of herbs, with a young Bride facing him, while she tries to understand what is so grave about simply knocking on the Mother’s door. I distinctly feel the water raising the keel of my book and I see everything setting sail again in the voice of the old man, who says…

– E