Date read: 8.13.10

Book from: Personal collection, via Conlan Press

Reviewer: Emera

This here’s the manticore. Man’s head, lion’s body, tail of a scorpion. Captured at midnight, eating werewolves to sweeten its breath…

The Last Unicorn comic adaptation #2 (review for #1) arrived at my door last week, and despite being exhausted I had to squeeze it in before falling asleep that night, in part because this is the issue that I can’t help but think of as “Meet Schmendrick,” and what self-respecting fan could resist the tawdry horrors of Mommy Fortuna’s carnival, to boot? In this issue, the unicorn wakes to find herself imprisoned in a two-bit witch’s menagerie of illusory monsters, and her best chances for escape lie with a well-meaning but inept magician named Schmendrick.

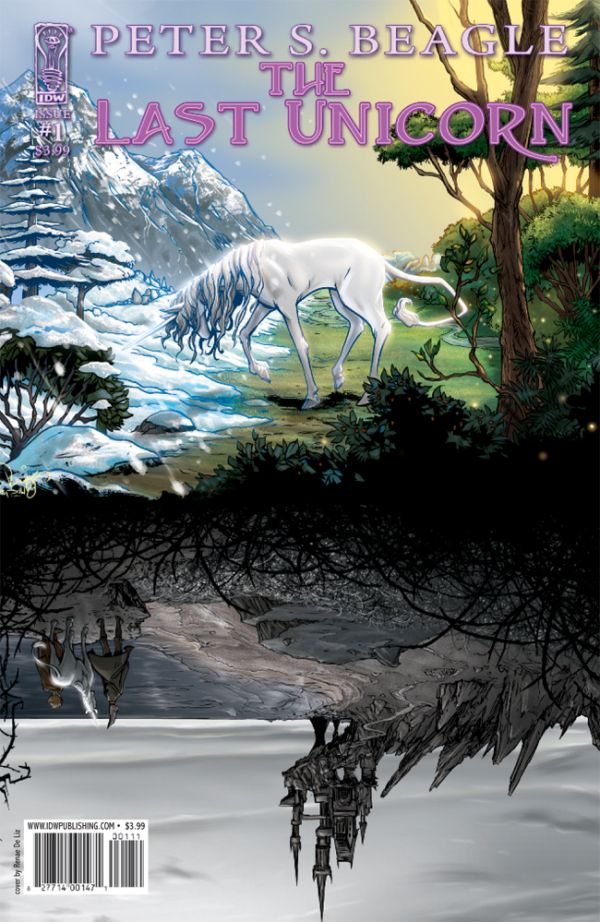

This time, I got Frank Stockton’s alternate cover art:

While I love his graphical approach, and particularly liked his cover variant for the first issue, it irks me that his unicorn tends to look kind of witless, and on principle I have trouble condoning the idea of a unicorn having “the hair of a Hollywood starlet.” Also, I really, really loved the de Liz/Dillon cover design for this issue. But life goes on, and Mommy Fortuna’s hand looks awesome here.

While I love his graphical approach, and particularly liked his cover variant for the first issue, it irks me that his unicorn tends to look kind of witless, and on principle I have trouble condoning the idea of a unicorn having “the hair of a Hollywood starlet.” Also, I really, really loved the de Liz/Dillon cover design for this issue. But life goes on, and Mommy Fortuna’s hand looks awesome here.

Basically, everything that I liked about the first issue I liked just as much, if not more, here: atmospheric color choices, expressive human characters, effective panel layouts, and pretty much pitch-perfect adaptation of the text. Very occasionally I was still bothered by coloring choices, but I found the use of textures much less obtrusive in this issue than in the first, and particularly effective in conveying the murk and grime of Mommy Fortuna’s carnival. There were also a couple of mostly-wordless compressions of action and narration that made me go YESSS, that could not have been done in any medium other than comics.