Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 4.18.2016

Book from: Personal collection

In their ruddy jackets of leather that reached to their knees the men of Erl appeared before their lord, the stately white-haired man in his long red room. He leaned in his carven chair and heard their spokesman.

And thus their spokesman said.

‘For seven hundred years the chiefs of your race have ruled us well; and their deeds are remembered by the minor minstrels, living on yet in their little tinkling songs. And yet the generations stream away, and there is no new thing.’

‘What would you?’ said the lord.

‘We would be ruled by a magic lord,’ they said.

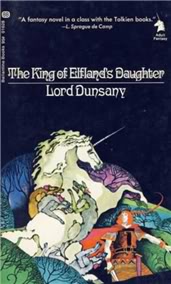

The King of Elfland’s Daughter is a dreamy, colorful, exceedingly British literary fairy-story for adults; it’s a crucial antecedent to the Lord of the Rings, Lovecraft, and other early purveyors of rich prose and high fantasy. I’d been meaning to read this ever since I started delving into Tolkieniana in high school, and saw it discussed in one of Tom Shippey’s essay collections, and finally invested in a personal copy when Seek Books liquidated a few years ago (alaaaas).

Previously, I’d only read one other bit of Dunsany – one of his short stories, likewise in a Shippey anthology that I picked out in high school. I remember the story as being pleasantly swampy, and involving big swords, at least one lizard-monster, and monolithic architecture. Great; carry on.

Elfland unfortunately I found a slog to get through, which is one of those things that makes one feel jaded. About once a chapter there’d be a human insight or a wondrous image that made me smile; the rest of the time, I found it terrifically cloying, and poorly paced and motivated. It seems to stagger back and forth in the territory between overexplained high fantasy and mystifying fairy story, such that it’s neither quite weird enough to fly free of expectations of logic, nor quite grounded enough in recognizable motivations to feel like much more than a succession of elaborate tableaux. I’d also argue there’s something rhythmically off about the delivery of the fairy-story elements, where the repetition and flow fail to build the kind of irrefutable dream-logic that pulls good mythos onward, but this could be a secondary symptom of my dislike for Dunsany’s writing on the sentence level.

The allover layer of pastoral treacle is what did me in from the beginning. (e.g., “little tinkling songs” above.) I have a tolerance for British plumminess that easily tips over into an embarrassingly active enjoyment (see: my ability to repeatedly reread Richard Adams’ epic fantasies), but Dunsany overleaps plumminess and stands firmly in the Land of Preciousness. So many buttercups.

Returning to the idea of generic contributions: it was interesting to recognize the eventual moral bent of the narrative – where magic/sense of wonder is a good in and of itself, and its restoration to a land is a triumph – as one that I had previously thought of as typical of later fantasy. (McKillip does this a lot, for example.) That is, I see that story structure as deeply indicative of a genre that is both conscious and defensive of itself of as a genre. It makes sense, then, that Dunsany would stand as a precedent to Tolkien et al. not only in style, but in literary ethos.

Related reading:

“The Golden Key,” by George MacDonald (1867) E