Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 11.2.2013

Book from: Personal collection

‘There are three things that grow in March Mire,’ said the aunt, in a silly sing-song voice, her eyes half closed, ‘and that grow nowhere else together, and seldom anywhere. Find them in one spot, take them and make them up. From them comes this dew. Oh Louisa. Listen carefully. This stuff grants the gift of death.’

Louisa widened her eyes but she was not actually impressed. Death was everywhere in the mire and especially often in her aunt’s nasty bottles.

‘Listen,’ said the aunt again, ‘the poison in this bottle leaves no trace as it kills. In the world beyond the mire this can mean much. I’ve told you, there are towns along the moors, and great houses piled up with money and jewels. If every cobweb on that ceiling was changed to bank notes it would be nothing to them … We’ll seek for just such a rich place. Then I’ll know how to go on. You shall pretend to be a lost lady, as I’ve trained you. You’ll do as I say, and our fortunes will be made.’

‘But how, Aunt?’

‘They’ll fall in love, and make over their goods through wills, which I’ve told you of. And then I’ll see them off …’

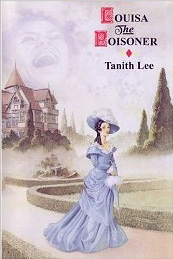

This standalone Tanith Lee novella from Wildside Press is quite as wicked and frivolous as it sounds. There’re vile aristocrats, bloody deaths, and incidental madmen and ghost horses; there’s brooding architecture (a manor called Maskullance!) and one of Lee’s trademark canny and uncanny heroines – those women who enter into society at an angle, slice their way in quietly. Also, George Barr provides some beautifully pulpy illustrations; his Louisa has a great Vivian Leigh-ish thing going on:

Unfortunately, the prose isn’t quite as effortless as it so often is in Lee’s work – the little twists of syntax often feel worked over, rather than sinuous and startling, and the dialogue frequently falls short of wittiness. And I think the story would have worked better at shorter length, given that a reading a detailed accounting of the sequential deaths of a bunch of boorish aristocrats entails spending a depressing amount of time with those aristocrats.

Still, the last few pages work up to a tremor of dreadful sublimity, and feature one of the best descriptions of hell I’ve ever read. If not one of Lee’s strongest works, this is nonetheless a fun treat for a cloudy autumn afternoon.

Go to:

Tanith Lee: bio and works reviewed