Date Read: 3.31.07

Book From: Personal Collection

Reviewer: Kakaner

Summary

Deeba and Zanna begin to experience strange phenomena until suddenly, one day, they find themselves in the alternate universe of Unlondon. Here they find that Unlondon has been waiting for a long time for Zanna, the “Shwazzy,” to fight the evil Smog, an evil cloud of pollution. However, things are not what they seem when events contradict the prophecies and Deeba is forced to fight the Smog on her own.

Review

I MISS BEING 12.

I have a feeling that if I read this while in middle school, I would have deemed Un Lun Dun The Best Book Evar. The book is incredibly reminiscent of Phantom Tollbooth, chock full of strange realizations of imagination, each a quirky interpretation of something we find in our reality. There’s not much to say plot-wise… the bulk of content was simply the adventure and development of Unlondon and numerous characters, a delightful afternoon romp for the appreciative reader.

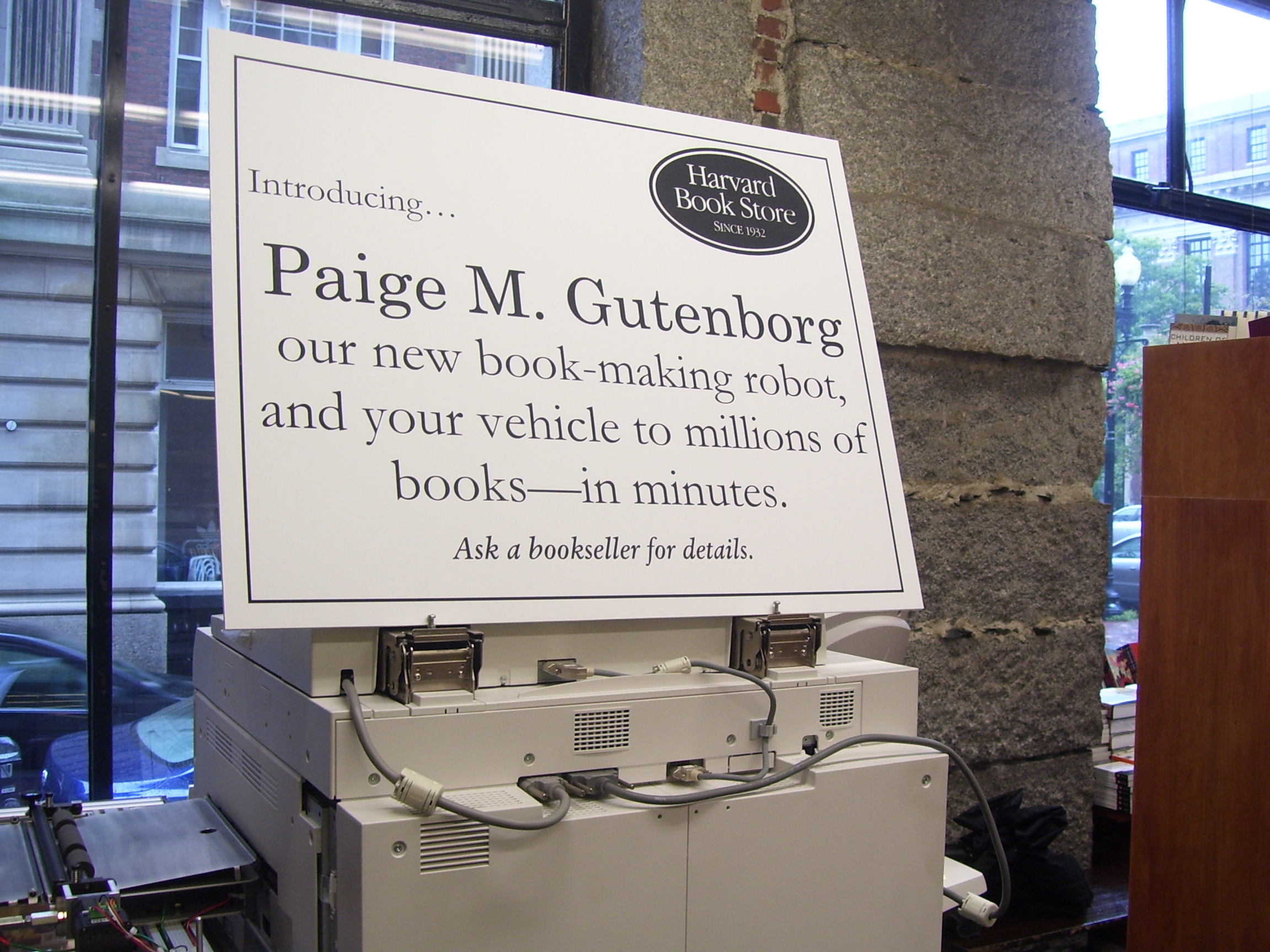

As I organized my thoughts for this review, I remembered the China Miéville event I attended at which I saw him speak about Un Lun Dun and the entire YA genre with vivid boyish excitement, and the memory is coloring my opinions of Un Lun Dun with much fondness. I crushed hard on the fact that so much of the humor and wit in Un Lun Dun was derived from references and puns concerning books. Some pun examples, though not necessarily book-related, are the Black Window, Unbrellas, and Bookaneers! But most of the circumstantial humor was centered around books, and made me suspect that Un Lun Dun was really a huge elaborate scheme to write a book to promote the message: “BOOKS ARE TEH SH*T!” and it made me extremely happy.

Unfortunately, I actually don’t consider Un Lun Dun a must-read. But if you’re a die hard Miéville fan, definitely check it out. The main character is very likeable, and it is an insanely easy read with maximum 4-page chapters. To top it all off, you get to see Miéville‘s very own original illustrations. There’s nothing better (or sometimes worse) than observing an author treading new ground, and Mieville does so quite expertly. There is indeed a deep understanding of the YA psyche and which elements excite the imagination.

Go to:

China Miéville

Un Lun Dun, by China Miéville (2007) E