Reviewer: Emera

Date read: Vars. in November and December 2017

Book from: Personal collection

The Dover collection of Best Ghost Stories of J. S. LeFanu (originally issued in 1964, with a rapturous introduction by an E. F. Bleiler, “an editor, bibliographer, and scholar of science fiction, detective fiction, and fantasy literature” according to Wiki) contains the following stories:

Squire Toby’s Will, Schalken the Painter, Madam Crowl’s Ghost, The Haunted Baronet, Green Tea, The Familiar, Mr. Justice Harbottle, Carmilla, The Fortunes of Sir Robert Ardagh, An Account of Some Strange Disturbances on Aungier Street, The Dead Sexton, Ghost Stories of the Tiled House, An Authentic Narrative of a Haunted House, Sir Dominick’s Bargain, Ultor de Lacey

…of which I’ve currently read all but “The Dead Sexton,” “Sir Dominick,” and “Ultor de Lacy” (which is what I’d like to name an S&M lingerie shop). (Note that LeFanu’s work is available online for free, being in the public domain.) Presently I’m in the middle of re-reading “Carmilla,” one of the only two stories I’d read before.Thoughts on some of the rest…

—–

I was a bit disappointed and perplexed by “Green Tea,” having heard that it was LeFanu’s most renowned story after “Carmilla,” and having been intrigued for quite some time by the seductively mysterious title. The central specter (which is not tea) is devilishly uncomfortable, and there’s a powerful sense of dark magnetism dictating the specter’s encounters with the narrator. (M. R. James’ unstoppable horrors later echo the same narrative rhythm.)

But I feel the story’s integrity is spoiled by the preening narration of Dr. Hesselius, LeFanu’s proto-Van-Helsing, who prides himself on his ability to counteract supernatural influences through rational medical practice. His flippant, self-congratulatory closing pontifications pretty well ruined the story for me, even if his final sentence is tasty:

“Thus we find strange bed-fellows, and the mortal and immortal prematurely make acquaintance.”

Talking-head Hesselius makes this story the most explicit enumeration of LeFanu’s supernatural principle, which would go on to inspire Lovecraft – that we are at all times surrounded by terrible sights and malign beings, but only certain states of physiological or psychological disturbance make us vulnerable to influences. This principle shows up explicitly in almost all of the stories claimed to have been drawn from Hesselius’ files, and I think one or two others as well. Personally I find it notable as a literary feature, but not interesting; it’s discussed too fussily to evoke a sense of dread.

—–

“Squire Toby’s Will” suffers from what I think is LeFanu’s most frequent narrative weakness: poor pacing. The opening scenes feel leaden and ungainly, and the feuding between the rival brothers at the plot’s center reads as failed comedy. But the story does draw atmospheric power (1.21 English Gothic gigawatts!) from its rainy, moldering setting and crabbed, ill-tempered characters. And as in “Green Tea,” the central specter is memorably uncomfortable:

The head of the brute looked so large, its body long and thin, and its joints so ungainly and dislocated, that the Squire, with old Cooper beside him, looked on with a feeling of disgust and astonishment, which, in a moment or two more, brought the Squire’s stick down upon him with a couple of heavy thumps. The beast awakened from his ecstasy, sprang to the head of the grave, and there on a sudden, thick and bandy as before, confronted the Squire, who stood at its foot, with a terrible grin, and eyes with the peculiar green of canine fury.

—–

Sticking with the theme of “critters,” “The White Cat of Drumgunniol” is a cross between a fairy tale and a vengeful-ghost story:

“There is a famous story of a white cat, with which we all become acquainted in the nursery. I am going to tell a story of a white cat very different from the amiable and enchanted princess who took that disguise for a season.”

The story opens with a lakeside scene witnessed by the narrator by a boy, and which I think is goddamn amazing – tense, eerie, calm, unbearably strange. (It reminds me of the climactic vision in I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House.)

The story decrescendoes from there, sustaining some of the tension and the chilly sense of otherworldly hostility, but terminating wistfully and weakly. The ending suits when the narrative is taken as the verbal account it’s purported to be, but, for a literary story, is disappointingly stingless.

Related reading:

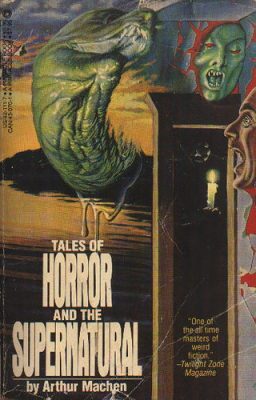

Tales of Horror and the Supernatural, by Arthur Machen (1948): review by Emera

The Haunted Dolls’ House and Other Ghost Stories, by M. R. James (1919, 1925): review by Emera

(I find this cover so upsetting)

(I find this cover so upsetting)