Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 4.30.2012

Book from: Personal collection

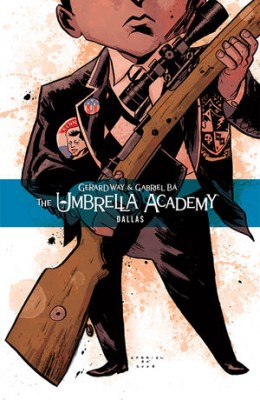

The Umbrella Academy: Dallas begins and ends with presidential assassinations; in between, a whirlpool of crises sucks in the already battered members of the Umbrella Academy superhero “family,” and spits them out again even more embittered and doubtful of their humanity. In between, there’s extensive time travel, nuclear annihilation, a brief interlude in heaven, a man with a goldfish for a head, and page after page of Gerard Way’s incredibly sharp, incredibly funny, incredibly on storytelling and dialogue. (I found myself wanting to deliver affirmations like, “Why yes, Gerard Way, a pair of Girl-Scout-cookie-obsessed hitmen WOULD sound exactly like that!!”)

The Umbrella Academy: Dallas begins and ends with presidential assassinations; in between, a whirlpool of crises sucks in the already battered members of the Umbrella Academy superhero “family,” and spits them out again even more embittered and doubtful of their humanity. In between, there’s extensive time travel, nuclear annihilation, a brief interlude in heaven, a man with a goldfish for a head, and page after page of Gerard Way’s incredibly sharp, incredibly funny, incredibly on storytelling and dialogue. (I found myself wanting to deliver affirmations like, “Why yes, Gerard Way, a pair of Girl-Scout-cookie-obsessed hitmen WOULD sound exactly like that!!”)

The presiding metaphor of this volume is of the jungle, and jungle beasts. (“I am in the jungle and I am too fast for you. You have teeth and stripes and things that tear. But I am much too fast… […] Only I know where the jungle is… only I know…” goes Number Five’s crazed self-paean as he single-handedly destroys an army of time-traveling enforcers. It’s both hilarious and chilling, in combination with Bá’s increasingly saucer-eyed rendition of Five and Dave Stewart’s lurid colors for the scene.)

Umbrella Academy works off of the psychological model for superheroes that’s prevailed since Watchmen: they’re average human beings – willful, petty, self-absorbed – acting out their neuroses and capacity for brutality, both emotional and physical, on superhuman scales. Kraken is the series’ Rorschach, obsessed on a primal level with vigilanteism. Spaceboy began as (to jump comic universes) the moody, nobly pathetic X-Man, ashamed of his physical monstrosity (his head was grafted to a Martian gorilla’s body in a lifesaving operation at some point in the past), but by the beginning of this arc has gone over to Nite Owl – overweight, impotent, haunted by crumbling ideals of heroism.

Spaceboy is an obvious visual manifestation of the jungle-beast metaphor: the superhero who’s at least as much monster as man, a Frankensteinian creation as cognitively dissonant and surreally comical as the intelligence-augmented chimps that now constitute a significant proportion of the world of the Umbrella Academy. The chimps were also experimental creations of the Academy’s founder, Sir Reginald Hargreeves, of course. The brief glimpses we get of frigid, controlling Hargreeves are some of the most disturbing moments of the series; it’s a wonder that the Umbrella kids, his grandest experiment, didn’t turn out even more dysfunctional.

In the end, disaster is averted and the world is saved, but at the cost of the life of a good man, and further erosion of the tenuous bonds among the Umbrella Academy. I was pretty heartbroken by the end of the volume, especially after the emotionally devastating bonus story, “Anywhere But Here,” which reveals a pivotal moment from Vanya’s past. Way and Bá have taken their superheroes to such depths of despondency that it’s hard to imagine where they’ll go from here, but I trust that they’ll continue to unfold their heroes’ fates with style, wit, and humanity.

Go to:

Gerard Way: bio and works reviewed

The Umbrella Academy, Vol. 1: Apocalypse Suite (2008): review by Emera