Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 11.21.2021

Book from: Library

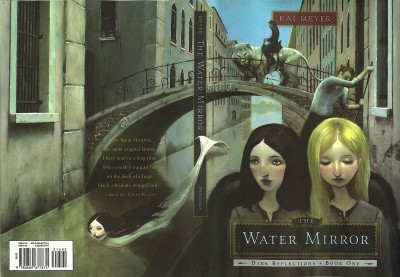

James Asher, a retired member of the Queen’s secret service in Edwardian England, has settled into quietude as an Oxford professor of philology with his physician wife, Lydia. But his peace is shattered when he’s confronted by a pale aristocratic Spaniard named Don Simon Ysidro, who makes an outlandish claim that someone is killing his fellow vampires of London, and he needs James’s help to ferret the culprit out. The request comes with a threatening ultimatum: Should James fail, both he and his wife will die.

Those Who Hunt the Night is dark, exciting, full of intriguing historical detail, intelligently written, character-driven, and yet ultimately a little vapid. It does exactly what it says on the box—Edwardian vampire murder detective novel!!!—and doesn’t exceed. I couldn’t stop reading it, and I was thrilled when I realized that it’s a full series of (so far) eight novels, but it wears its indulgent nature both a little too openly—and yet not flagrantly enough. It’s like… tame pulp? Tidy pulp?

The first couple of chapters are weighed down with brow-furrowing exposition, and the character descriptions throughout are several shades too affectionate and repetitive. Red-headed Lydia is almost always described as “waifish” or “deer-like;” I swear there isn’t a single line about Ysidro that doesn’t mention how pale and remote he is; etc. At the same time, it’s not so indulgent that it tips over into the deliciously campy realm of something like Anne Rice’s vampire novels, so it ends up feeling prim. I suppose that suits the scholarly nature of the novel’s protagonist.

The closest comparison that I can draw is to Kage Baker’s steampunk novella series The Women of Nell Gwynne’s: adventurous, socially aware, biased towards bookish characters, and ultimately a little light and silly despite ostensibly dark subject matter. This may be exactly what some readers are looking for, of course; I would have loved something wilder and meatier.