Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 4.18.2019

Read from: The New Yorker

I didn’t realize that Shirley Jackson’s children were still discovering unpublished stories of hers; the New Yorker has published two in recent years, “The Man in the Woods” and “Paranoia.”

“The Man in the Woods” is a delightful choice for a stand-alone publication. Tense, elegant, and cryptic, its dense mythological and folkloric allusions beg for toying and unpicking – even if its determined evasiveness means that it is not sharply compelling as a work of psychological fiction. If it were presented in a collection, it would likely sink into the shadow of any of Jackson’s more spectacularly psychological stories. But even taking it simply as a sort of playful, appreciative remix of a handful of dark folkloric tropes, it stands out as being pretty much perfect on a line-by-line level: economical, vivid, and singing with tension.

The cat had joined him shortly after he entered the forest, emerging from between the trees in a quick, shadowy movement that surprised Christopher at first and then, oddly, comforted him, and the cat had stayed beside him, moving closer to Christopher as the trees pressed insistently closer to them both, trotting along in the casual acceptance of human company that cats exhibit when they are frightened.

The two stories that immediately popped into my head when reading this: Angela Carter’s “The Erl-King” (a previous, brief appreciation here) with its likewise claustrophobic trees and its building towards the inevitability of kingly sacrifice; and Hansel and Gretel. In fact, with regard to Hansel, I was sure at first that this was going to be “just” a witch-story, and that the two otherworldly women whom Christopher meets in the stone cottage in the woods would be joined by a third – Hecate. So it was a strange little thrill when the third in the house turned out rather to be a Mr. Oakes: a green-man, and a sacrificial priest-king straight out of Frazer’s The Golden Bough.

Fans of Elizabeth Marie Pope’s Tam Lin retelling, The Perilous Gard, will be well familiar with the reading of “Christopher” as “Christ-bearer” specifically in the context of pagan sacrifice. Her Christopher, like Jackson’s, is a youth who offers up to pagan captors the temptation of a double sacrifice – an intermingling of two different sacred powers – through the symbolic weight of his name.

Though Jackson’s protagonist Christopher offers this tantalizing symbolism (“‘Christopher,’ [Mr. Oakes] said softly, as though estimating the name”), he’s otherwise strangely devoid of anything resembling narrative or, let’s call it, a symbolic system. He carries the modernish signifier of having been at “college,” and allows that that loosely qualifies him to be deemed a “scholar” by Mr. Oakes. But he doesn’t know why he left college and started wandering, and he doesn’t know what to name a cat other than “kitty.” So far as personality is concerned, he is careful, courteous, and expresses glints of humor and curiosity, including a faint appetite for the younger woman, Phyllis. But it’s all diffused through a screen of something like mild dissociation, or at least ennui. He seems like a refugee from the modern world, stripped of meaning and motivation.

His encounter with the household in the wood seems destined to force him into meaning, just as his unnamed cat attains the witchy title of “Grimalkin” by displacing the household’s original cat. In the end, Christopher follows along with a sort of tranced acquiescence.

But even assuming that his challenge of Mr. Oakes will be successful, it’s unclear whether this new (ancient) system of meaning will be any more compelling than whatever he left behind in his old life. Phyllis, Circe, and Oakes seem listless and weary. (Only Circe, appropriately, shows a trace of defiance: “Circe I was born and Circe I will have for my name till I die.”) Oakes, despite his name, doesn’t seem any more fond of the woods than Christopher is; he plants roses as a challenge to their oppressiveness. Civilization, it seems, erects various defenses against the void, but over time they all grow, as Hamlet put it, flat, weary, stale, and unprofitable. They become oppressions of their own.

Final note: they were totally eating the previous challengers –

“…Phyllis, sent to fetch a special utensil from an alcove in the corner of the kitchen, came back to report that it had been mislaid “since the last time” and could not be found…”

“…Aunt Cissy disappeared into the kitchen alcove again and came back carrying the trussed carcass of what seemed to Christopher to be a wild pig.”

Related reading:

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson (1962): review by Emera

Angela Carter’s “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon”

A very happy October to all

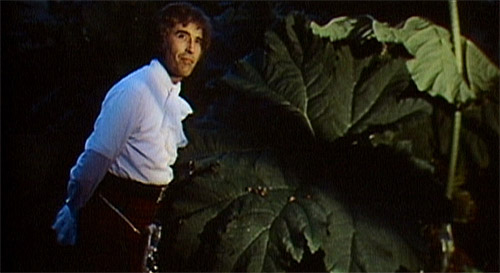

“Where is Rowan Morrison?”