Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 10.2016

Book from: Library

Rat Queens is a rambunctious Dungeons ‘n’ Dragons parody featuring a gang of ultraviolent, foul-mouthed lady adventurers: Hannah the moody, uptight elven mage, dwarven warrior Violet (pictured above with her orc boyfriend Dave), escaped-from-a-Lovecraftian-cult cleric Dee, and candy/hallucinogen-obsessed smidgen (i.e., halfling) Betty. In Volume 1, the Queens deal with the consequences of their inability to rein in their penchant for destructive brawling, which has earned them enemies within the walls of their own town. In volume 2, the airing of old grudges escalates to the summoning of Lovecraftian beasties; the ensuing ruin is intercut with flashbacks that begin revealing the younger lives of most of the Queens.

Rat Queens is inextricably linked with Brian Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ Saga in my mind: they’re both recent Image comics that feature racially/sexually diverse casts, obstreperous women, “pretty” art with a light anime influence, sarcastic humor, and graphic violence. In that match-up, though, Rat Queens comes up lacking. Wiebe writes pretty awkwardly at times, and tonally, the comic is in that regime of sarcastic trope-busting where if you’re even slightly not feeling it, it just comes off as try-hard.

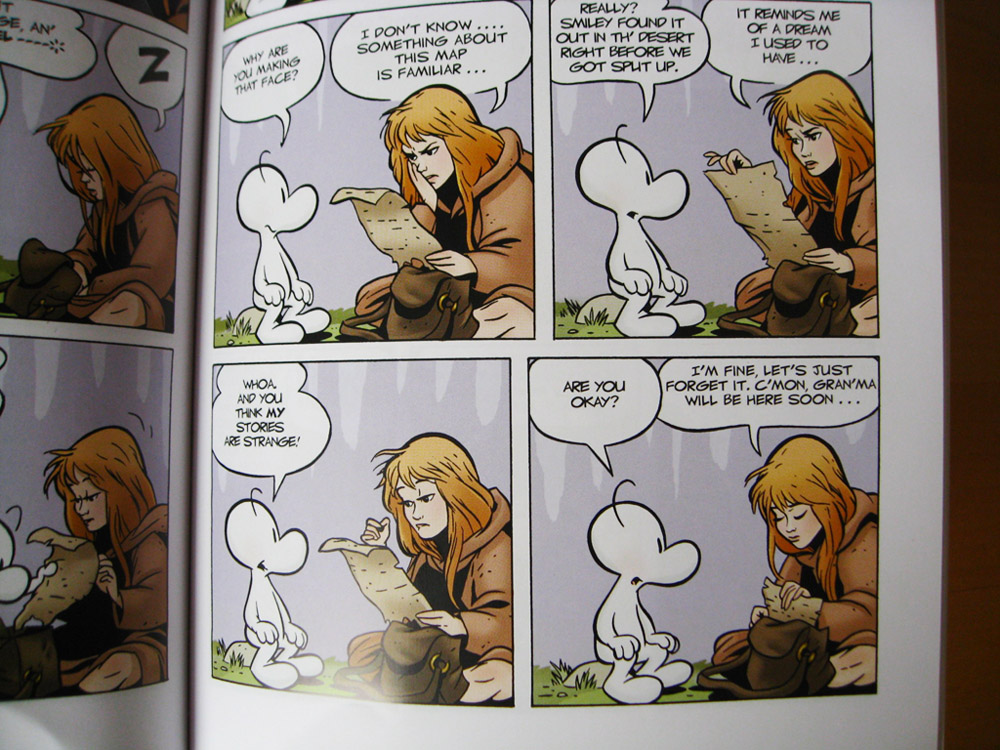

In terms of art, Upchurch is likewise okay. He’s good at facial expressions, and occasional panels are quite pretty, but his art often mashes down into strange scribbled shapes that betray a mediocre sense of volume and anatomy. The backgrounds are weak as well; they often feel kind of incoherent and joylessly drab to me. Here’s a representative Upchurch page – theoretically pretty chicks with wandering facial features, backgrounds blurred beyond usefulness:

Stjepan Sejic picks up art duty partway through Volume 2: Kurtis removed Upchurch from the series after he was confirmed to have committed domestic abuse. Sejic, not Upchurch, is responsible for the cover art featured up top. Sejic’s work is strong – seductively painterly and with great taste in color and light, as evidenced by the cover – and he’s an excellent match for the comic thematically since he’s done a number of hilarious trope-busting joke comics. His only obvious weakness is his inability to draw kids without them looking like creepy adult heads pasted onto miniature bodies. My understanding is that unfortunately Sejic departed the series after Vol. 2 due to work conflicts.

But between Sejic’s work and increasingly substantive storytelling, the comic did grow on me as I dug into Volume 2. That whole volume felt narratively solid to me: the character development is thoughtful, mostly dwelling on issues of authority, belonging, and trust (familial, cultural, religious), and also deepened my appreciation of the Rat Queens’ friendships.

Still, I think I could drop this series without feeling like I’d missed that much. First, the interpersonal conflicts, while humanely portrayed, are pretty standard for fantasy (“I’m an outsiderrrrr”). (I think a significant part of why Saga is so unique and successful is that Vaughan investigates familial relationships in a much more specific and personally informed manner, rather than drawing from the typical sff stockroom of Generic Angst Causation.) Second, there isn’t yet a compelling overarching external conflict. Finally, though I feel fondly towards several of the characters (mainly Dee, Hannah, and Braga), I’m not so invested that I feel the need to keep reading just to see what happens to them.

Altogether, I’d call this fun but not unmissable. Blessings on the proliferation of media focusing on female protagonists, though.

Go to:

Saga, vol. 1, by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples (2012) E

On the road to Saga

Bone, Volume 1: Out From Boneville

Bone, Volume 1: Out From Boneville