Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 5.11.2012

Book from: Personal collection

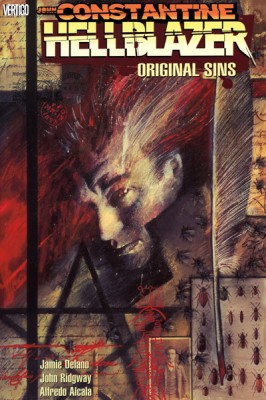

Original Sins collects issues 1-9 of Hellblazer, written by Jamie Delano, with art by John Ridgway & Alfredo Alcala.

There’s a certain disadvantage to targeted reading of comics (or whatever) that are considered to be gamechangers. This is, obviously, that you don’t actually appreciate what the game is that they’re coming along and changing. I theoretically know plenty, for example, about what the 1980’s British Invasion of Comics achieved, and I’ve consistently enjoyed the associated works. But since I don’t actually want to go sloshing around in the surrounding milieu of stagnating American comics, I just have to take people’s word for it that they were stagnating – which means that it’s hard to completely understand what the Brit Pack reacted against so successfully. Ah well.

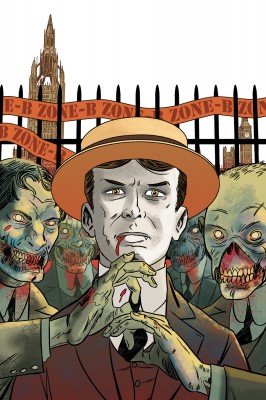

It’s a rotten, fallen world that magician John Constantine lives in, ushered along by his ripely tortured narration (“My mouth is rank – sweat bathes me, like the cold, nicotine condensation on the carriage window”), and sometimes simply by panel after panel depicting British urban misery in Ridgway and Alcala’s scratchy inks. Delano takes shots at just about everything awful in Britain (and sometimes the US) in the ’80’s, sometimes satirically (demon yuppies!) and sometimes just angrily: Maggie Thatcher, economic decay, televangelism, football hooliganism, and hatred and bigotry and greed of all stripes. I’ve seen the John Constantine character dismissed as dated, but it’s depressing how close to home much of Original Sins still feels in 2012, particularly on the economic front.

It’s the anger that really gets to you in this series, anger directed both outward and in. Constantine often lashes out against the forces of suppurating evil, but even more often seems to do harm to humanity himself through some combination of deliberate, self-interested inaction and plain cockiness. Apparently it’s a running “joke” in the series that Constantine gets all of his friends killed; he’s already off to an impressive start in Original Sins, with various allies falling dead throughout the volume at the hands of all manner of hellspawn and religious zealots. His raffishness and devil-may-care pragmatism too often translate into willingness to pass easy judgments on others’ weaknesses, and on what needs to be done to expedite his idea of the greater good, with the result that guilt becomes another dominating flavor of the series.

The story that I found the most viscerally disturbing in the volume, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” features Constantine as passive witness to the destruction of an Iowan town by their own Vietnam War ghosts. He insists that he’s cut off from the conflict, helpless to intervene. But given his shoddy track record on intervention throughout the volume, I wasn’t so convinced that this wasn’t just his well-developed sense of self-preservation talking.

I was certainly impressed with the heated, fetid atmosphere that Delano brews up – so different from the limp, humorless chilliness of the Constantine movie, whose main and only attraction for me was the Keanu-Reeves-as-Constantine/Tilda-Swinton-as-Gabriel homoerotic tension. Unfortunately, my aggregated puzzlement at the dense referencing of previously encountered characters and situations increasingly convinced me that I really had to backpedal at least a couple years and start in with Swamp Thing, where John Constantine first appears, before diving back into Hellblazer.

I also note that I started this review a year ago, and, coming back to finish it now, find that my memories of the comic are surprisingly dim. I’m guessing that this is in large part because I felt more impressed by its effect, than actually affected.

Go to:

Jamie Delano: bio and works reviewed

Violent Cases, by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean (1987): review by Emera