Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 5.19.13

Book from: Personal collection

I expected Sakuran to be fun – racy, rambunctious, ornate. Brothel life in Edo-era Japan, oh yeah. And it is fun, sort of – bubbling over with scheming, ambition, spectacle, and biting exchanges of emotional violence.

But it’s also deeply, and more lastingly, sad. Kiyoha is fifty times the usual feisty protagonist: she’s crass, arbitrarily malicious, and often outright violent. While this can all be amusing, even admirable, it’s also a disturbing, straightforward statement about the molding influence of a system founded on mistrust, competition, and the basic cruelty of buying and trading young women. Sure, Kiyoha might just be a queen of cats by inclination, but we also bear witness to the events that progressively eat away at her humanity, at her willingness to trust and share and be kind.

The courtesans’ lives are haunted by a desperate craving for love, and by its impossibility. If I recall correctly, only one of the girls eventually marries her favorite patron; the rest are fated to disappointment, or even death, at the hands of patrons, or their own desperation. The manga culminates in a quiet emotional ruin: in a few pages, we see Kiyoha – at the ripe age of twenty-something – eaten completely hollow by love’s casual betrayal. Sakuran is an anti-romance, in other words.

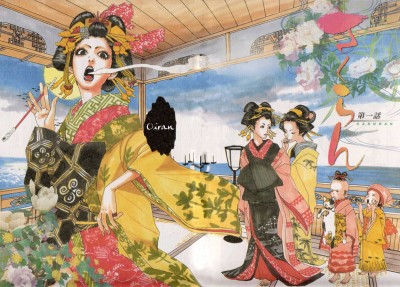

While I have nothing but praise for Sakuran‘s emotional daring and honesty, there are several practical stumbling blocks to enjoying the manga. Moyoco Anno draws only a veeeery narrow range of facial features, so it’s nearly impossible to distinguish the oiran (and many of their patrons, too) except by their wardrobes. Flipping frantically between pages to double-check which girl with what dialogue bubble had the kimono with the crane pattern and not the peony pattern and these hair ornaments not those hair ornaments, was about as fun as it sounds – and then you get to do it all over again as soon as the scene changes and everyone’s wearing different clothes! Which happens often, since the manga drifts from vignette to vignette, with little connective tissue. This works to create a sense of drifting and dislocation, of the oiran existing in an unmoored twilight realm whose essential drudgery is punctuated by episodes of bizarrely heightened emotion. But my god, it wouldn’t have hurt for everyone to look a little bit more different, would it?

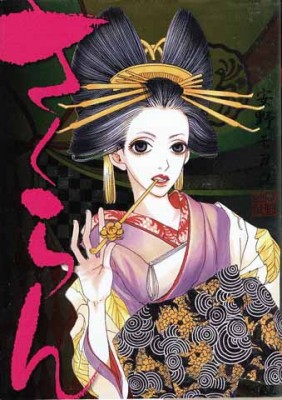

Productionwise, there’s a lot to love about Vertical Inc.’s sophisticated visual design, as usual (ohhhh that glamorously garish metallic cover), but I wasn’t entirely satisfied with the translation. While a certain degree of informality seems apropos to the manga’s earthiness and irreverence, many of the anachronisms (“spacing out,” “twerp”) just seemed silly and misplaced. And, too, most of the lyrical reflections don’t quite reach the height of fluency and elegance that they need to work as emotional transitions between scenes; they contort into fortune-cookie-esque awkwardness, e.g. “Castle-topplers whisper idle nothings to trap their guests.”

Still, the underlying substance of the manga is so very excellent that it more than made up for all the practical distractions; I look forward to the added fluency of comprehension that a reread will bring. If you didn’t like Memoirs of a Geisha (I didn’t), or maybe if you did, too, but are ready for a more hard-bitten take on the courtesan-memoir, I strongly suggest you give Sakuran a try.