Reviewer: Emera

Date read: Nov. 2016

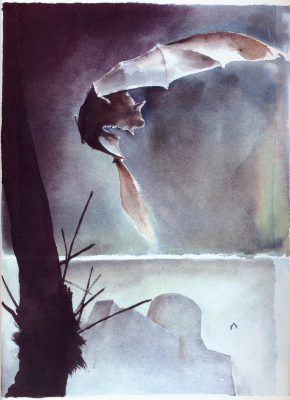

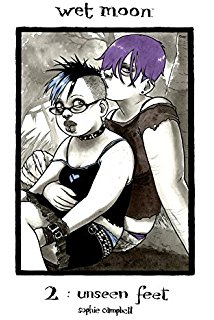

I’ve enjoyed the work of Sophie Campbell (formerly Ross Campbell) for 12, 13 years maybe. In high school I spent hours poring over the endless portraits (almost exclusively Wet Moon characters, at the time) in her deviantART account – humid, sexy, angsty, a little uncomfortable, very Goth, all executed in her trademark style of mostly monochrome ink and marker, with lots of lovely wash textures. There was a lot going on that you didn’t see much of in comic art those days – chubby girls, black girls. I was fascinated almost equally by the bodies and the fashion – hair, piercings, soft thighs under ripped fishnets – of all those languorously sprawling, sulkily self-possessed, implicitly vulnerable girls (and very occasional androgynous boys).

I have no good reason for why it took me so long to actually read Wet Moon, except that it used to be harder to find comics from smaller labels.

In the time since, Campbell came out as trans. To put it baldly, this presented an easy resolution to my one discomfort with Campbell’s work: that it could come off as voyeuristic, or fetishistic. To have a lingering male gaze suddenly revealed as [trans]female – suddenly consumption, desire, appreciation, longing are all construed so, so differently. Finding out that Campbell had come out as trans remains the most interesting shift I’ve ever experienced in my perception of an artist and their relationship to their work.

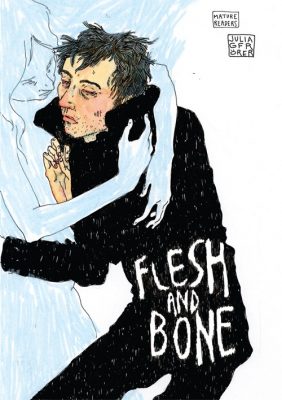

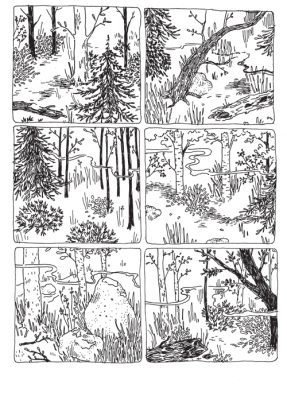

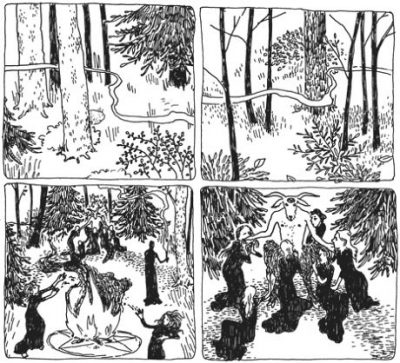

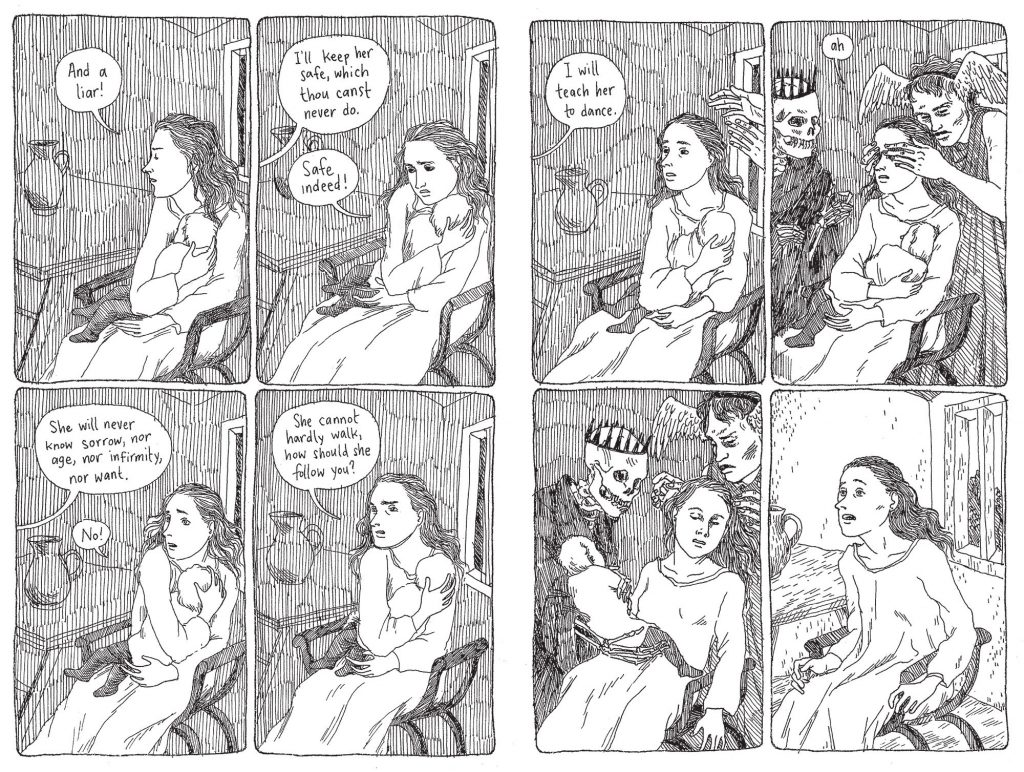

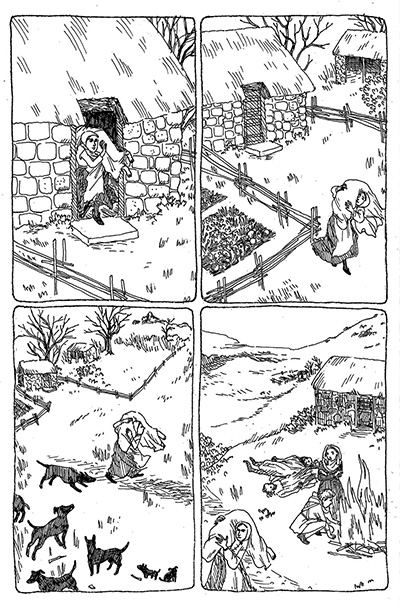

Wet Moon is a dark, dreamy slice-of-life comic, featuring a cast of southern, small-town punks, Goths, and art students, almost exclusively women, and heavily queer. Flavors: cigarettes, hairdye, patchouli, art-supply-store air, pie, swampwater. I’ve also seen comparisons to Twin Peaks, though being only two volumes in, the implied supernatural/mystery element is very slight. There’s a missing student who left a strange dark circular stain on her apartment floor, for example, and inexplicable, moonstruck behavior performed by various characters – midnight swamp immersions, ritualistic circling in front of windows. It’s all lovely and unsettling, and reminds me of, yes, the earliest episodes of Twin Peaks, where I had no idea what was going on, and small moments were rendered all the more terrifying because of it. (Those shots of the traffic light at night, for example – I don’t think I’ve ever been more afraid of what a traffic light might mean.)

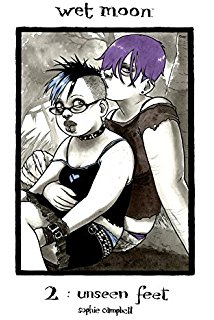

The protagonist is Cleo Lovedrop (yes, all of the characters have wonderful, absurd names – Malady Mayapple might be the winner), with the blue forelock on both of the covers above. Her struggles with romantic confusion and low self-esteem have so far provided the most obvious or continuous dramatic impetus for the series. But the drama is deliberately minimal; the interest lies more in mood, in the understated sense of mystery, and in the affectionate evocation of the banter – listless, playful, or barbed – and small upsets within an extended network of friends.

And then, much of the series so far has been implicitly about bodies: resenting them, costuming them, wanting them to be something different, subjecting them to long minutes of mute observation and appreciation. Multiple characters receive scenes of self-examination in mirrors: sucking in stomachs, examining scars, trying to make muscles. Most of the characters are overweight; some have disabilities or deformities. There’s so much bodily difference that different becomes the order of the day. The cumulative effect is, again, lovely; all the soft curves and folds and rumpled, revealing clothing contribute their own sense of soft melancholy.

Wet Moon is a unique and soulful work of art; I’m grateful that it exists. Scuttlebutt suggests that the series does become plottier, or at least more overtly dramatic – as a devoted fan of plotlessness, I’m almost disappointed, but obviously excited too for whatever Gothic mayhem awaits. Now it’s on me to track down the remaining four volumes (hopefully in the updated editions, with Campbell credited as Sophie, and some great cover designs by Annie Mok); volume 7 is still being eagerly awaited.

Related reading:

Wolf in White Van, by John Darnielle (2014) E