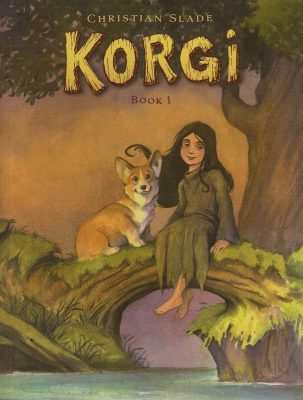

Korgi, by Christian Slade (2007): The woodland escapades and scrapes of a fairy-like young girl and her magical corgi companion – corgis were traditionally said to be fairy steeds. There are three volumes so far; I’ve read the first two.

This would be a great gift for folks, children or otherwise, who are keen on fairies and/or dogs. Korgi is so cute and so peaceful – nearly as cute as Mouse Guard, and whimsical, dreamy, and celebratory of motion in a way that’s reminiscent of a lot of the first volume of Flight. Slade is not a very good draftsman (wandering facial features + an overall look that is slightly squishy and uncertain), but every panel is well-composed, again and again hitting that evocative sense of marveling at a woodland expanse. Also, his linework is notably enjoyable – scratchy, nervy, woodsy. His treetrunks are so nice.

Something that Slade does really right is letting loose when drawing the villainous critters – their gleeful bloat and gnarl works well to counterbalance the wide-eyed sweetness of the rest of the comic.

—–

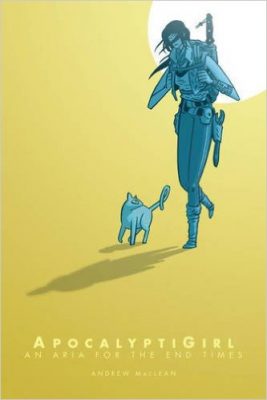

ApocalyptiGirl, by Andrew MacLean (2015): A beautiful, energetic, but morally questionable post-apocalyptic yarn of a young warrior woman and her cat surviving amid tribal warfare.

Read it for the crisp action sequences, expressive characters, and scruffy, nubbly, involving environments (rusting, grass-overgrown mechs; a home built in an abandoned subway train). The story’s mysteriousness is dampened by exposition that manages to be both heavy-handed and slightly garbled, and by the pat ending, which seems to lazily undercut all of heroine Aria’s past moral quandaries over the bloodshed she’s seen and enacted.

Still, the ambience and visuals are striking and memorable; I’m very happy to own the comic to keep revisiting the art.