Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 10.19.2021

Book from: Library

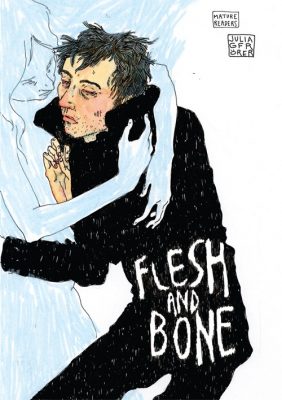

Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides is one of the most ecstatically beautiful, dream-like, and mournful books I’ve ever read, up next to Lolita. The two work together well in so many ways: the cuttingly yet not wholly satirical paean to the promise of America; the drenching languor and lust; the pathological yet resplendent objectification of beautiful, inaccessible girls. There’s a bit of Poe in there, too: the Gothic obsessiveness, the unreliable narrators.

The novel centers on many of the same themes as Eugenides’ Middlesex, but it’s much tighter, less sprawling, less broadly tragicomic. The single bullet in a revolver loaded for Russian roulette seems like an appropriate metaphor—elusive yet potent.

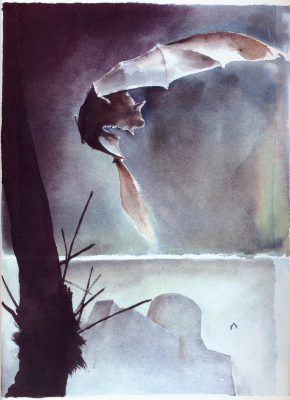

From a craft perspective, there was so much I admired about this book: sentence after sentence that floats and twists with metamorphic elegance and surprise; image after image of nightmare-dreamish beauty and suffering. (The final paragraph of the book gives me a wave of goosebumps every time I read it.) There were moments where Eugenides’ fabulist or magical-realist leanings put me in the same space as the horror movie It Follows. The queasy, desperate image of Lux Lisbon copulating on the roof of her parents’ house, night after night, blended in my mind with the scene in It Follows where the entity stands naked on a neighborhood rooftop, looming and improbable. The shadow of sex, death, and disorder falls over suburbia.

The book’s narrative technique, Eugenides’ choice of a “we” perspective (whose identity and role become clearer and clearer over the course of the novel) is quietly astonishing, hypnotic, and unnerving. It might be this choice that does the most work to lend the book its ineffable quality. We hear the story of a neighborhood as filtered through a shifting surveillance network, an aggregate view that is ultimately fallible, individual, and selfish, yet by assuming the status of “we” insists on a semblance of omniscience and authority.

This paradox of collective identity seems like the crux of the novel, and Eugenides plays on it in several configurations: through the narrating “we;” through the despairing alliance of the Lisbon sisters; and through the social landscape that surrounds them, the tidy suburbia crumbling at the edges, where the decay and racial tension of neighboring Detroit seep through. Every union is imperfect; everything contains the seeds of entropy.

Related reviews:

Picnic at Hanging Rock, by Joan Lindsay (1967)