Date read: 8.2.10

Book from: Borrowed from a friend

Reviewer: Emera

Apparently not a single unpixellated version of this image wants to let me find it.

Whyyyy did I read this all in (pretty much) one sitting. Whatever the opposite of feel-good is, MW falls into that category. The whole time I was reading, I got the impression of Tezuka Osamu crowing, “Suffer in an agony of dread while I, the creator of such lovable, family-friendly classics of Japanese animation and comics as Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, manipulate your feelings with this unrelentingly dark thriller about a serial killer and the priest bound to him by guilt and love! Bwa ha ha ha!” Thanks, Tezuka. By the time I hit the last 20 pages, I was so overwrought with fatalistic dread that I had to put the book down for a few hours, before returning to the equally depressing final scenes.

For an illuminating bit of background, Wikipedia provided me with the following context: “This manga series is notable because it can be seen as Tezuka’s response to the gekiga (“dramatic pictures”) artists who emerged in the 1960s and 70s and an attempt to beat them at their own game.The gekiga artists of this period created gritty, adult-oriented works that sharply contrasted the softer, Disney-influenced style that Tezuka was associated with, a style that was seen as being out-of-step with the times.” So I think I’m not entirely wrong in detecting a certain amount of authorial glee in the proceedings.

MW is also a response to the use of chemical weaponry during the Vietnam War. MW‘s resident sociopath, Yuki Michio, the charming, long-lashed scion of a renowned family of kabuki actors, is a sociopath because he was exposed as a child to a neurotoxic weapon – MW – leaked from an island containment facility owned by Nation X (i.e. America). Father Garai, Yuki’s confidante and extremely guilty lover, feels bound to protect Yuki’s identity from the authorities because he, as an erstwhile hoodlum, was holding a nine-year-old Yuki captive at the time. He and Yuki were the only survivors; Garai joined the Church some time thereafter in an attempt to escape both his horror at having witnessed the disaster, and his guilt at his relationship with Yuki. (Yes, do the math there. Tezuka reaches for pretty much every variety of shock value, and even by the standards of anime/manga, most of it is awful.)

Over the course of the manga, Father Garai is repeatedly guilted and blackmailed into aiding Yuki in his course of destruction. Garai at first believes that Yuki seeks to expose and bring down those responsible for the MW leak and its subsequent cover-up, but eventually learns that Yuki perpetrates his varied murders and extensive political manipulations with worse and wider goals in mind.

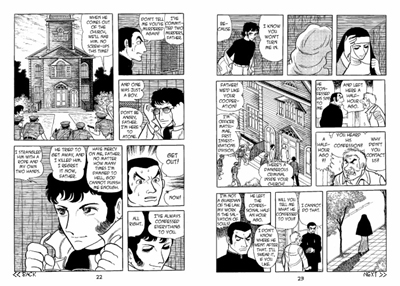

Yuki and Father Garai’s first exchange in the manga.

Tezuka’s elastic, broadly expressive art makes for a really bizarre contrast with the manga’s subject matter. At times the cartooniness undercuts the drama and emotional impact of some of the scenes that should be genuinely moving or frightening; at other times, it’s an unnerving counterpoint. Having read only one other Tezuka manga (Black Jack), and that a number of years ago, it was a pleasure to see classic manga style in action again. Every scene is finely detailed, and mostly in ink, without the reliance of contemporary manga on screentones for shading. It’s also really, really nice to actually be able to tell characters apart by traits other than their hairstyles. (Facial features? What are those?) Also also, there’s one spread in which every panel is modeled after Aubrey Beardsley’s work, which first made me go “whut,” and then be pleased, if still lingeringly nonplussed.

As a story, MW is exceedingly tightly plotted, and if many of its twists are predictable, at least they’re dramatically compelling. A lot of the police procedural work that goes on is laughable – I was particularly bothered by how stupidly easy it would have been to avert the final twist – but at a certain point I just shrugged and sat back to enjoy the spectacle. The nonstop intensity is addictive, and many of the characters are complex and believable in their flaws.

Tezuka’s treatment of Garai’s homosexuality is also plainly sympathetic, and yields a few surprisingly tender scenes. Possibly my favorite sequence in the entire series was one in which a female newspaper editor refuses to run incriminating photos taken of Father Garai in a gay club; later, she goes home to her lover, who’s revealed to also be a woman, exclaiming, “You wouldn’t believe the good deed I did today!” It’s an unexpected touch of sweetness in a series otherwise ruled at best by black humor and at worst by hatred for humanity.

I would tentatively recommend the manga for fans of Urasawa Naoki’s Monster, as I found it hard not to draw thematic and plot comparisons between the two while reading, though MW, with its theatricality (I allllmost want to call it camp), fails to be as moving.

Kudos to publisher Vertical Inc., finally, for publishing MW as one hardcover volume. It’s both more attractive and easier to read than the usual tightly-bound softcover manga volume, not to mention cheaper than an equivalent set of separate volumes would have been. Also, though I disliked pretty much all of the font choices, the translation was uniformly excellent, so kudos again on that point.

Go to:

Tezuka Osamu

One thought on “MW, by Tezuka Osamu (1976-1978) E”