Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 11.23.11

Book from: Personal collection

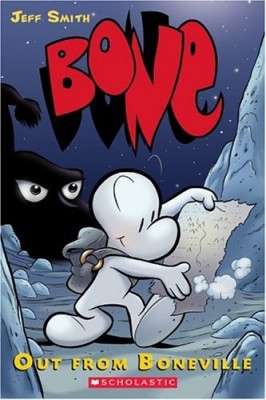

Bone, Volume 1: Out From Boneville

Bone, Volume 1: Out From Boneville

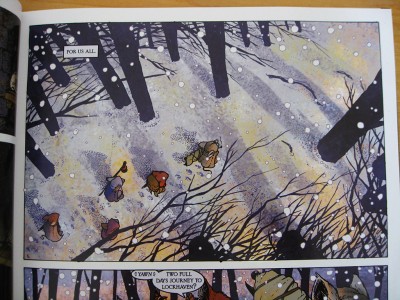

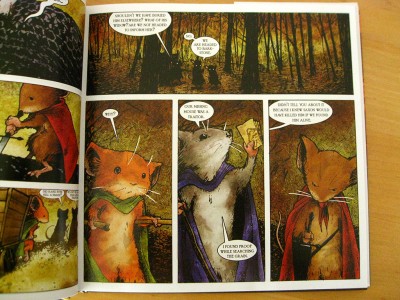

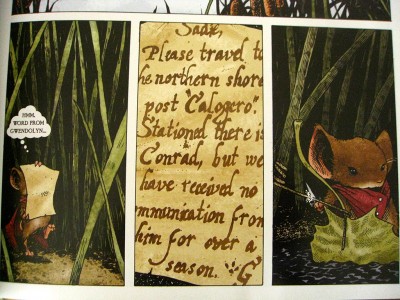

“After being run out of Boneville, the three Bone cousins – trusty Fone Bone, grasping Phoney Bone, and obliviously cheerful Smiley Bone – are separated and lost in a vast, uncharted desert. One by one, they find their way into a deep, forested valley filled with wonderful and terrifying creatures. Eventually, the cousins are reunited at a farmstead run by tough, cow-racing Gran’ma Ben and her spirited granddaughter, Thorn. But little do the Bones know, there are dark forces conspiring against them and their adventures are only just beginning…”

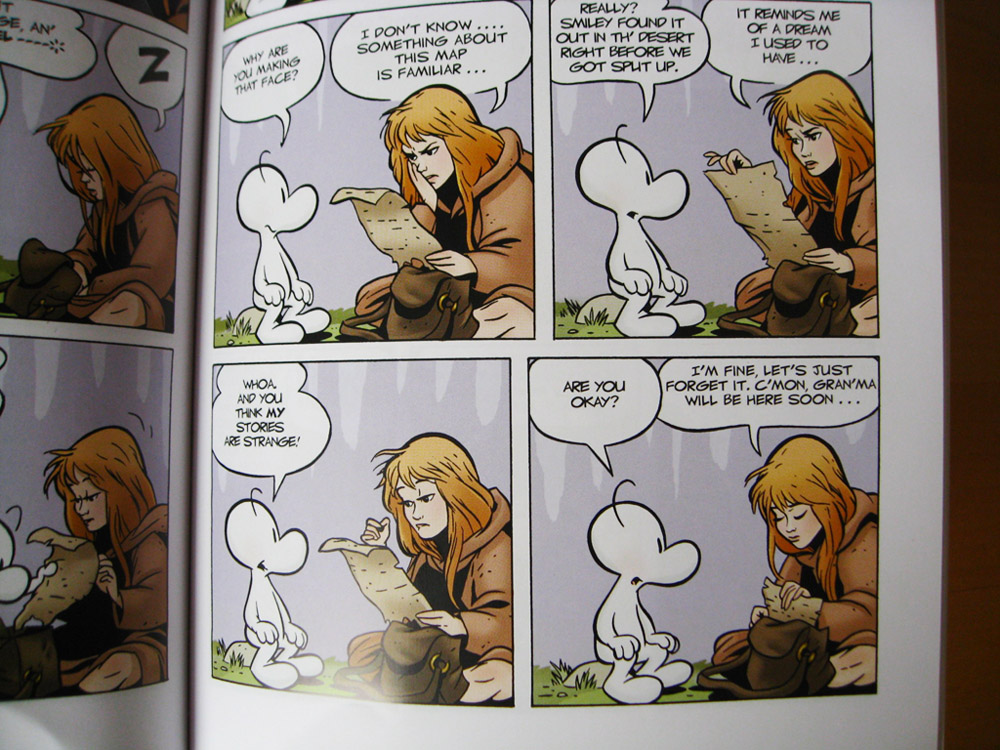

Late to the bandwagon as usual! I’d wanted to read the ever-popular Bone saga for years, and was lucky enough to find a slightly battered copy for half-off while comic-shopping recently. The first volume instantly brought me back to reading Asterix comics on the couch in second grade: Smith’s old-school art is fluidly expressive and filled with gentle slapstick and visual gags. (A recurring one: whenever he’s overcome by his crush on Thorn, Fone Bone’s mouth crumples up into a scribbled line, and he litters the area with trails of pink hearts.) It’s just comforting to read, sweet, funny, and expertly paced – a good old-fashioned adventure to enjoy on a sunny afternoon.

While I don’t feel too driven by the storyline yet (seems like war with the carrion-eating rat creatures lies ahead), I do love the oddness of the world: the way the seasons arrive with comically accelerated timing in the valley, talking katydid Ted and his giant cousin, the introduction of comics and paper currency (the latter with less success) to the valley inhabitants by the Bones. What exactly is the relationship between the valley and the external world, and what, really, are the Bones? I’m eager to see what comes along, especially if it involves more Gran’ma Ben thonking rat creatures.

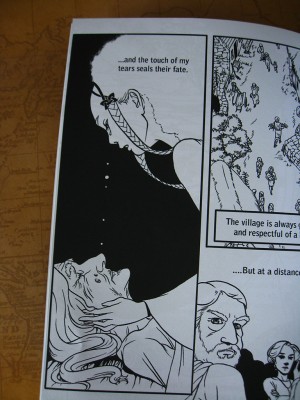

And my favorite sequence of art: the evolution of Thorn’s facial expressions and hand gestures on this page (click for a close-up of the whole page).