Date Read: 6.10.09 (fourth[?] reread)

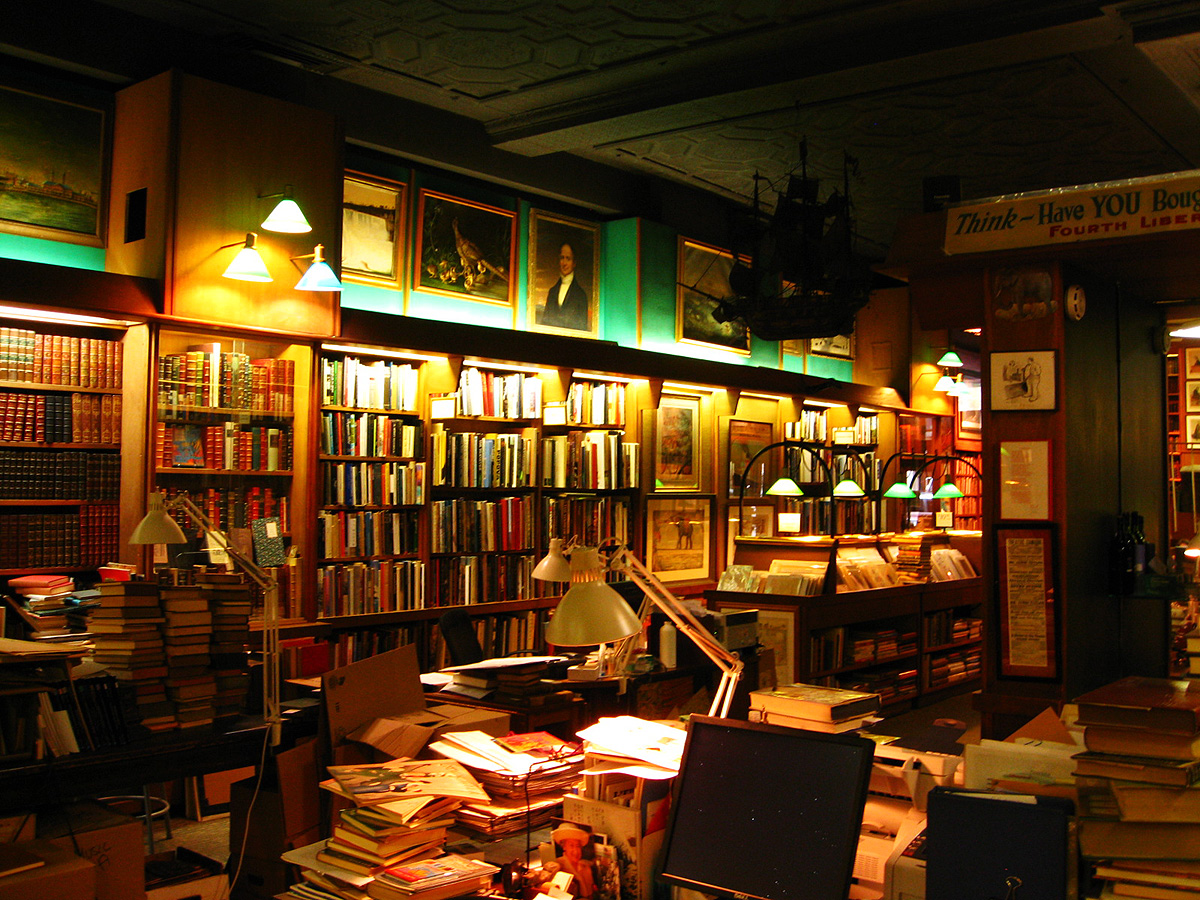

Book From: Personal collection

Reviewer: Emera

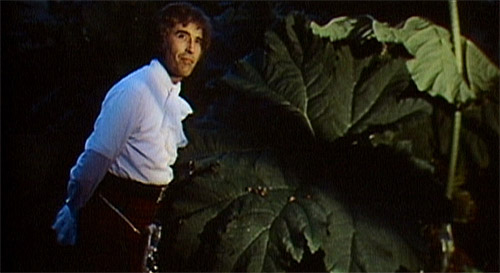

Caribou is a dreamer of dreams, a solitary figure isolated from her tribe ever since the death of her father. One day her sister-in-law comes to her, bearing a strange golden child whom she begs Cari to conceal and raise. At first unwilling, Cari is nevertheless struck by the child’s beauty and takes him in, naming him Reindeer – for as she reluctantly comes to realize, he is a trangl, one who can take the form of both human and stag. Though she longs to keep him by her side, his blood will always call him to run with the wild deer that course the land. As the years pass, stirring spirits and strange upheavals in the mountains and hot springs send the tribespeople to Cari’s door for advice. From Reindeer, she learns that the world is being remade, and that if she is to save her people, she and Reindeer must guide them over the Burning Plains to the safety of the lands that lie beyond the Pole, where only the wild deer have run before.

Of all the authors I’ve read, I’ve most deeply identified with the work of Meredith Ann Pierce, for the longest period of time. I first read her books when I was eight or nine, and though there were many literary loves before then, and have been many, many more since, I always think of Pierce’s books – particularly her Darkangel Trilogy – as The Milestones. She’s most often written tales about strange, wise girls who become strange, wise women, fall in love with transfigured or supernatural lovers, and have adventures in worlds of beautifully realized mythology. Mythology, because her books often read to me like myths from alien planets: her images and language have a timeless, jewel-like purity to them, coupled with deliciously archaic diction and – this might be the part that most gets me – a deep, deep sense of yearning that encompasses both human and immortal desires.

This was the first time I’ve re-read one of her books in about eight years, and since a lot has changed in that time, this doesn’t have quite as immediate an emotional impact on me as it used to. I used to get a lot of vicarious rage and anguish on Cari’s behalf. The older me is both slightly more phlegmatic (though really not that much less romantic), and slightly savvier: this time around, I was a little squicked at Cari having a relationship with her foster child, despite Pierce’s care in emphasizing his inhuman nature and unfamilial relationship with Cari.

Regardless, I was still deeply affected by the wondrous and joyful imagery: gambling trollwives, rivers of silver caribou running, a sledge with belled harness and golden runners, firelords with lava-seamed palms… And while the younger me fumed (again on Cari’s behalf) when she read the inconclusive ending, the older me was pleasantly surprised to recognize its maturity and realism. This will continue to be a story, and a world, that I treasure, and that I suspect will still surprise me every time I re-enter it.

Meredith Ann Pierce’s works will very likely appeal to fans of Patricia McKillip and Robin McKinley; I’ve never entirely understood why she hasn’t become more well-known and widely read. Not that I’m biased or anything.

Go to:

Meredith Ann Pierce