Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 5.10.2017

Book from: Personal collection – grateful thanks to C. for this gift!

Something is rotten at Crook, the decaying English manor house that is the setting for McGrath’s exuberantly spooky novel. Fledge, the butler, is getting intimate with the mistress. Fledge’s wife is getting intimate with the claret. Sidney Giblet, the master’s prospective son-in-law, has disappeared. And the master himself – the one-time gentleman naturalist Sir Hugo Coal – is watching it all in a state of helpless fury, since he is paralyzed in a wheelchair, unable to move or speak.

The Grotesque is simultaneously a whodunnit and pageturner (though from the start it’s insisted that we believe that it was, in fact, the butler), and a thorny psychological thicket of doubles, shape-shifting, adultery, and madness. It made me think of a sniggering, Gothic cousin of Brideshead Revisited, as they share the snarled-up Roman Catholic British aristos, the homoeroticism, the acute class anxiety, and the character of an impish, loyal, dark-haired daughter. “Grand Guignol edition of Wodehouse” also covers it rather well, especially when it comes to names – Sidney Giblet you’ve seen already, and the local village is called “Pock-on-the-Fling.”

The book’s not even 200 pages long, but every page is thick with wordplay (Sir Hugo, for example, puns on his entrapment within the “grottos” of both his own skull and the nook under the stairs where his wheelchair is often left – I had forgotten that “grotesque” comes from “grotto”) and psychological feints. The narrative dodges back and forth across time – a structure that Sir Hugo claims to be a function of his increasingly unreliable wits, but of course also results in the juiciest revelations being put off for last.

I enjoyed the heck out of this elegant mess, and read the first half especially with slightly unhealthy speed. I had to do a bit of thinking about why I didn’t utterly love it, and I think it comes down to the style: I crave continually surprising language, which in Gothics tends to translate to “really florid.” McGrath’s writing is very fine, with physical descriptions of characters being especially sharp and memorable, but for me, the imagery only rarely and the language never hits the heights of the sublime. This might be a constraint of character, as Sir Hugo prides himself on his cold-blooded propriety of thought; I’d have to read more McGrath to see whether his style has broader range.

The freshest and most lastingly troubling element of this book for me was the thematic stuff around ontological confusion. Sir Hugo’s background as a gentleman naturalist, and his morbid embrace of the physical facts of reproduction and decay, provide fertile grounds for elaboration on this sense of “the grotesque.” That is, the grotesque is also “a 16th-century decorative style in which parts of human, animal, and plant forms are distorted and mixed.” Sir Hugo, the paralyzed would-be paleontologist, is neither animal nor vegetable nor mineral. Described as involuntarily grunting like a pig, and “a vegetable,” and “ossified,” he eventually converges with the looming figure of his beloved dinosaur fossil, which by the end of the novel has grown a drapery of lichen due to neglect and damp. Sir Hugo’s neurologist dismisses him as “ontologically dead” – but internally, Sir Hugo shoots back that “I was, I believe, the most ontologically alive person in that room.”

All these uneasy mutations and meltings of category are artistically impressive, but also simply, humanly sad. The most cutting scene of the book for me was the one in which Sir Hugo reflects on how quickly his household writes him off after his accident. Setting aside the fair question of whether Sir Hugo, bastard that he is, might deserve much of what happened to him, this is really sharp, sad writing about the emotional reality of human disability and decline:

“In fact, it was one of the most striking aspects of that first stage of my vegetal existence, the experience of seeing my family’s reactions shift from grief and compassion to acceptance and apparent indifference in a remarkably short period of time. Thus, I notice, are the dead forgotten; thus are persons in my state rendered tolerable… Our kinship with the grotesque is something to be shunned; it requires an act of rejection, of brisk alienation, and here the doctors were most cooperative, for they permitted Harriet and the rest of them to reject my persisting humanity by means of a gobbledygook that carried the imprimatur of – science! … [S]cience proposes, this is how I had lived, but science also disposes, and now I find myself frozen, stuck fast, like a fly in a web, in the grid of a medical taxonomy. My identity was now neuropathological. I was no longer a man, I was an instance of a disease…”

This furious sorrow struck me as some of the only genuine emotion in a narrative otherwise composed mainly of self-absorption and guilty half-truths.

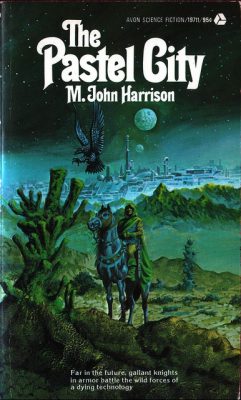

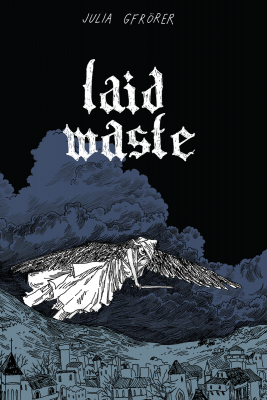

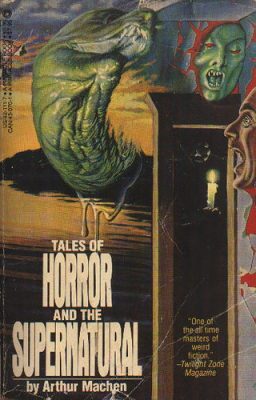

(I find this cover so upsetting)

(I find this cover so upsetting)