Reviewer: Emera

Date read: 11.4.11

Story from: Read it online here

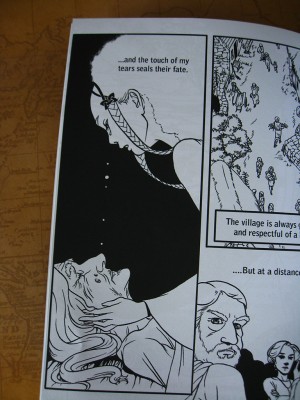

“… The owners of Harrowby Hall had done their utmost to rid themselves of the damp and dewy lady who rose up out of the best bedroom floor at midnight, but without avail. They had tried stopping the clock, so that the ghost would not know when it was midnight; but she made her appearance just the same, with that fearful miasmatic personality of hers, and there she would stand until everything about her was thoroughly saturated.”

“The Water Ghost of Harrowby Hall” (1894) is one of the most hilariously prim ghost stories you’ll ever read, a sort of ghost story of manners:

“You are a witty man for your years,” said the ghost.

“Well, my humor is drier than yours ever will be,” returned the master.

“No doubt. I’m never dry. I am the Water Ghost of Harrowby Hall, and dryness is a quality entirely beyond my wildest hope.”

It also makes itself an easy target for feminist readings – the ghost, a “sudden incursion of aqueous femininity” (!), repeatedly intrudes on the Harrowby masters’ cozy quarters with her indiscriminately sloshy woes… (Aligns well with Chinese ghost traditions, too – tsk tsk, so wet, not enough masculine principle.)

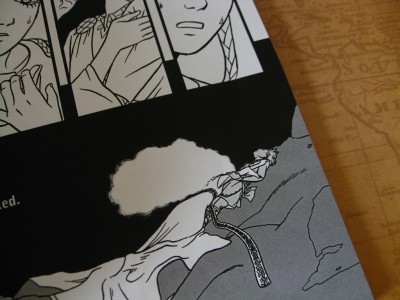

The twist introduced in the last paragraph ends the otherwise trifling story on a surprisingly sinister note. It’s a troubling moment that drags the faintly misogynistic tone of the story’s proceedings to the foreground, and leaves them hanging there for your consideration.

This version of the story online includes some charming illustrations, but lacks the final paragraph, without which the story is far less interesting.