Date read: 3.20.10

Book from: Personal collection

Reviewer: Emera

In the chimney the autumn wind sings the song of the elements, and the old firs before my study window wave excitedly with their arms and sing so loudly in chorus that I can hear their sighing melody through the double panes. Suddenly from above, a dozen black, streamlined projectiles shoot across the piece of clouded sky for which my window forms a frame. Heavily as stones they fall, fall to the tops of the firs where they suddenly sprout wings, become birds and then light feather rags that the storm seizes and whirls out of my line of vision, more rapidly than they were borne into it.

[…]

And look what they do with the wind! At first sight, you, poor human being, think that the storm is playing with the birds, like a cat with a mouse, but soon you see, with astonishment, that it is the fury of the elements that here plays the role of the mouse and that the jackdaws are treating the storm exactly as the cat its unfortunate victim. Nearly, but only nearly, do they give the storm its head, let it throw them high, high into the heavens, till they seem to fall upwards, then, with a casual flap of a wing, they turn themselves over, open their pinions for a fraction of a second from below against the wind, and dive – with an acceleration far greater than that of a falling stone – into the depths below. Another tiny jerk of the wing and they return to their normal position and, on close-reefed sails, shoot away with breathless speed into the teeth of the gale, hundreds of yards to the west: this all playfully and without effort, just to spite the stupid wind that tries to drive them towards the east. The sightless monster itself must perform the work of propelling the birds through the air at a rate of well over 80 miles an hour; the jackdaws do nothing to help beyond a few lazy adjustments of their black wings.

Konrad Lorenz (1903-1989) was a Nobel-prize-winning Austrian ethologist (animal behaviorist) particularly famous for his work on imprinting, and is one of the loves of my life. He’s wonderful to read – wise, methodical, wondering, and wryly humorous. Being guided through his observations is like an act of meditation, and every chapter in King Solomon’s Ring (whose title refers to the mythical ring that allowed Solomon to speak with animals) bears multiple, slow re-reads.

The chapter I quoted above, “The Perennial Retainers,” is about the jackdaws in the eaves of his mansion in Altenberg, and is the most emotionally powerful chapter, because of Lorenz’s intense and life-long love for these complex birds. My other favorite chapter deals with his painstaking care and observations of a litter of minute, high-maintenance water shrews. Given that water shrews are nearly blind, Lorenz’s extensive consideration of their navigational abilities is particularly fascinating.

Lorenz also discusses the intricate ecologies of aquaria, the heritage of the domesticated dog (though I’m not sure whether all of his theories on this have held up under genetics), violence in animals (including humans), and the lives and behavior of dozens of other species, from waterfowl to the venomous, voracious larvae of the Dytiscus beetle. All of this is peppered with various hilarious anecdotes, frequently about the lengths to which he went in order to assure his animals’ well-being: e.g. scaling his roof while dressed up in a devil costume in order to relocate some jackdaw chicks without their parents learning his actual appearance, only to be spotted, crouching on the rooftop, by a crowd of terrified villagers.

I was occasionally uncomfortable with the degree of anthropomorphism that creeps in, but generally Lorenz resists inappropriate anthropomorphizing, and indeed makes numerous incisive observations about the ways in which humans are prone to misinterpreting animal behavior and intelligence because of their propensity for anthropocentrism. Anyway, it’s hard to begrudge what here reads as the inevitable product of decades of intent study and deep appreciation, rather than as uninformed sentimentality. King Solomon’s Ring is, above all, a work of love; it’s a mind- and soul-feeding kind of book.

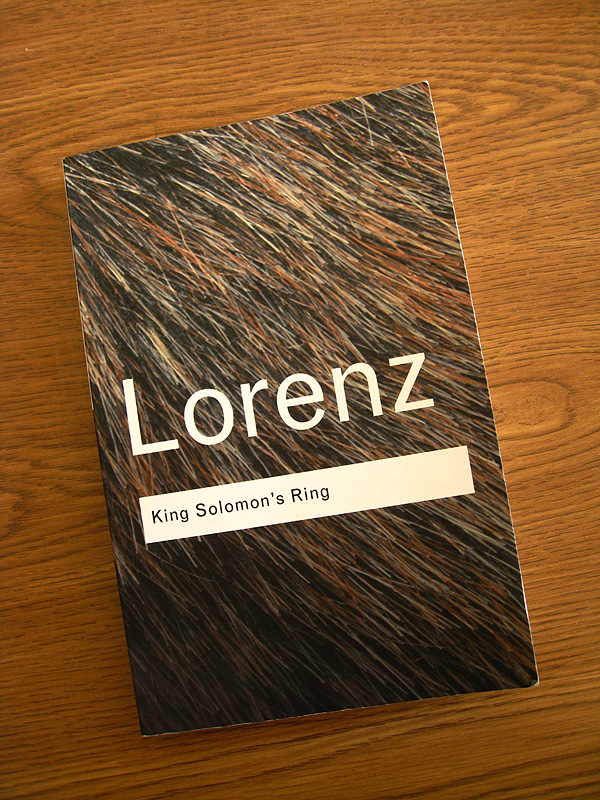

Also, I’m in love with the cover design of this edition, which also includes Lorenz’s amusing original illustrations (which I stupidly forgot to take pictures of).

[Also also, this is our 100th review post!]

Go to:

Konrad Lorenz

I got lost in those excerpts, and not the good kind of lost, the “my world is being engulf by flowery adjectives and commans” lost. I’d have to read this short bursts.

I will agree, the minimalist cover jacket is very well done.

Most of the writing isn’t this effusive; I just picked this section because I couldn’t find anything easier to quote, since the impact of a lot of the other sections is contingent on a lot more information. Possibly that was miscalculated, as most of his writing is really clean and simple. Sorry for the adjective overload!