Date read: 1.24.11

Book from: University library

Reviewer: Emera

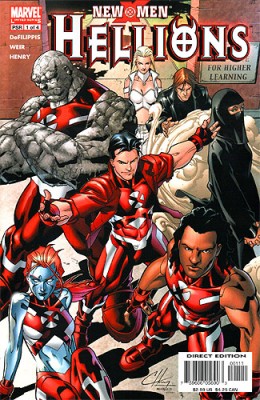

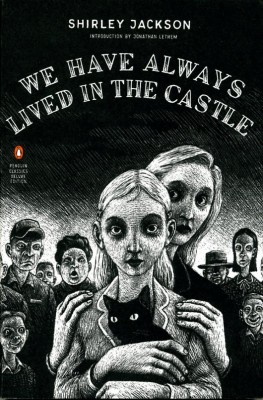

Penguin Ink editions, when will you stop being awesome? Cover art by Thomas Ott.

Penguin Ink editions, when will you stop being awesome? Cover art by Thomas Ott.

Shirley Jackson is the queen of opening lines:

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in our family is dead.”

We Have Always Lived in the Castle was the capstone in my mini Jackson-marathon of January; for some reason I’ve decided to review it first. It was her last novel, and contains almost all the Jackson trademarks: persecutory villagers, a haunted (not literally, in this case) house, thinly veiled wickedness and brutality, a split psyche, embodied here in sisters light and dark. Jonathan Lethem’s excellent introduction in the Penguin Ink edition situates these usefully in Jackson’s own life as the formerly shy wife of a university professor isolated in small-town New England, and in her sad decline as she succumbed to agoraphobia in her later years.

Merricat Blackwood. Oh, Merricat. She’s a typical Jackson heroine in that she’s determinedly childish and presexual; it’s hard not to read her relationship with the Blackwood house (like that other great Jackson house, Hill House) as an attempt to return to the womb. I also had a hard time remembering that she’s supposed to be 18, and not 12 or 13. A capricious, spiteful witch-child, she delights in hiding, in secrecy, in burying and nailing charms around the family estate, repeatedly drawing lines of protection around her and Constance and the house. (When interloping cousin Charles appears, Merricat hates him almost more for resembling her and Constance’s father than for his obvious mercenary aims; she strenuously rejects any masculine influence from their domain.) Her black cat Jonas follows her everywhere, and they “talk” to each other fluently. She loves thinking about the deaths of others: of her family, scandalously and mysteriously poisoned six years ago; of the villagers who hate them and blame fearful, fragile Constance for the murder. Above all, she’s monstrously selfish, a sort of funnel constantly drawing off Constance’s maternal attentions and lovingly described cooking.

Like any good trickster character, she’s both hateful and seductive. I couldn’t not identify with her flighty witchery – a good chunk of my childhood in a nutshell – all the while that I was increasingly repulsed by her emotional stranglehold on Constance. The violence in the book crescendoes shortly before the end, but the ugliness goes on from there, quietly, as Merricat proceeds to get exactly what she wants; it left me feeling more disturbed by a book than I have for a long while. At the same time, I couldn’t help remembering how much fun Merricat was, her wicked humor and her mocking embrace of dysfunction. Lethem’s introduction highlights Jackson’s talent for slyly “instill[ing] a sense of collusion in her readers,” reflecting “the strange fluidity of guilt as it passes from one person to another.” You can’t get much better at that than Merricat Blackwood.